What would you do to make a difference?

After his best friend Norah was almost abducted, Cole Nicholaus has spent most of his childhood homeschooled, lonely and pining for Norah to move from best friend to girl friend status. When birds follow him around or he levitates the dishes, he thinks nothing of it—until a reporter appears and pushes him into making a choice: stay safe at home or help save a kidnapped kid.

Cole and Norah quickly end up trying to not just save a kid, but an entire town from a curse that has devastating roots and implications for how exactly Cole came to be the saint that he is.

Can Cole stop evil from hurting him and Norah again? And maybe even get together? Only the saints know.

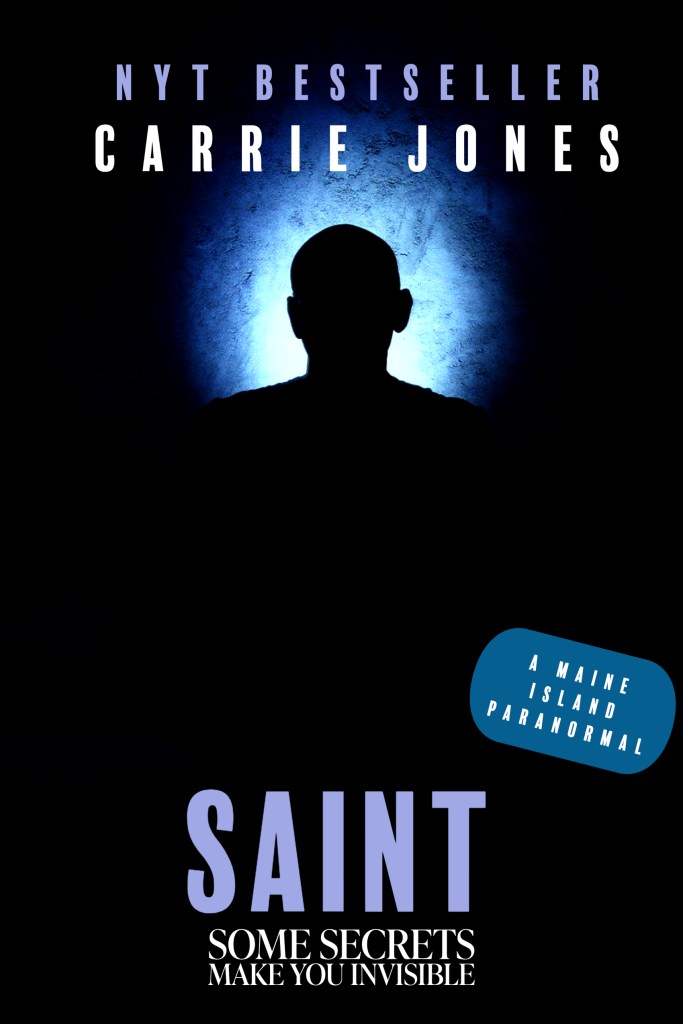

From the New York Times and internationally bestselling author of the NEED series, Saint is a book about dealing with the consequences that make us who we are and being brave enough to admit who we love and what we need.

YOU CAN BUY IT HERE! RIGHT NOW! 🙂

You can read the first chapter behind the jump.

Chapter 1

The birds tap at the kitchen window with tiny beaks. They hover there above the azalea bush and the still-to-bloom tiger lilies, wings wide open, eyes staring inside at where Mom and I bustle around our little white kitchen. They smack and caw and coo. There are seagulls, pigeons, crows, a couple of hummingbirds, a few owls, robins, blue jays, finches, doves and a random eagle tonight. All of them coexisting in some sort of peaceful bird truce. All of them watching us.

“Hey guys.” I give them an air first bump that I hope is cheerful. “Everything is okay.”

So, yeah, things are a bit bizarre around here, and Mom’s worried that I may not be able to handle it. This isn’t just because I have a tendency to levitate. And it isn’t because a news reporter has noticed that I exist, and it isn’t even that I seem to have ridiculously randy feelings about my best friend, Norah. My mother, thank God, does not know about that last part. No, she worries because of the door upstairs and the birds that are appearing absolutely everywhere all the time now.

“I am so tired of those darn things and their—and their—and their defecation.” She puts the stress on the last word of the sentence, wrinkling up her long nose. “It’s impossible to get it off the deck. And the chirping and squawking.”

She crosses herself.

We are Catholic and Mom has this weird nervous habit where she crosses herself all the time. She honestly is a bit like a bird herself as she flits around the kitchen. Her feet barely seem to touch the tile as she flutters from stove to refrigerator to sink to utensil drawer and back again in this endless pattern of frenzy amidst the white cabinets and stainless-steel appliances. It’s the opposite of me. I am a straight-line mover and all about solid, forward motion.

“I’ve been thinking about things,” I announce, taking a stool at the kitchen island as she opens the dishwasher. Steam drifts into the air. She avoids my eyes as she starts putting the dishes away. It takes her forever before she says, “Mm?” which means she’s listening and has steeled herself against any potential conflicts we might engage upon. She knows me well.

For the last eight years, which means since I was eight, Mom has believed that I need to be carefully watched over. So, I am home schooled because regular school was “too full of potential violence.” Every year, I attempt to change her mind, which is what I am doing now while she puts away dishes.

“I don’t think I socialize enough,” I argue. “I need to know how to deal with evil principals, and conniving teachers, which is an essential life skill.”

“You have plenty of time for that,” she says, putting a big soup pot on the stove. “How about some help with this?”

“And what about bullies? I have to learn how to thwart bullies.”

“Cole. The dishes.” She jumps as a woodpecker knocks against the window. “Shoo! Shoo!”

“Mom. You’re worrying about dishes when we’re talking about my socialization skills and the future impact of me not having to deal with jerks on a daily basis. Plus, I need to go to driver’s ed, which is at the school. Some guy who used to play minor league ball in Portland teaches it and – ”

She throws up her hands in an exasperated way. “There is housework to be done, Cole. Things have to be put away.”

“But this is my life. My existence. Don’t you want me to be prepared?” Guilt is an unfair weapon. I know this. But you have to use what weapons you have in your arsenal. A pitcher uses every pitch they have, right?

Before my ploy can work, however, her attention is drawn to the window where there are literally about thirty robins in hovering positions, staring inside.

“Oh my word! Those birds!” Grabbing a dishtowel, she starts to try to shoo them away. “Go! Scat! Stop staring!” She glares at me and pauses for a second in her bird battle. “Why must they find you so interesting?”

“If I was at school, they’d be there instead, I bet. They’d leave you alone. They would just follow me. Therefore,” I stress that word, “you should allow me to go to school.”

“That is your argument?” She blinks, a lock of hair falling into her forehead. She hoists the dishtowel and flops it over her shoulder, leaving it there, dangling.

I lean against the counter in a way that I hope looks confident. “Yes. I think it’s quite good actually.”

“Cole, you drive me insane. I love you, but you drive me insane.” She turns her back on the birds. “And I’m hardly likely to give in to this—this—this ridiculous demand of yours if you can’t even help me with the damn dishes.”

In the next second, the dishes all flutter up from the already open dishwasher. The silverware moves in rows through the air like a marching army. In perfect order, the forks, spoons, bread knives, steak knives, all fall into the drawer in their proper places, clanging and clanking against each other as they land. The dishes float like flying saucers, which I guess they technically are. They land more softly in a stack in the cabinet. The glasses line up in rows. However, the Mr. Spock Star Trek glass lands with Spock’s face turned to the back, which is just not right. The glass lifts an inch off the cabinet shelf, rotates into proper position and then settles back down. You have to give the emotionless Vulcan from the original series the proper respect.

“There,” I announce, still leaning. “Done.”

She hastily draws in her breath, shakes her head at me, and mutters, “Show off.”

I haven’t always been able to levitate things. I wasn’t a baby in my cradle cooing at rattles and making them hover over the mattress or anything weird. When I was a toddler, I didn’t make my teddy bears do a mid-air polka when I was bored. That would have been nice though. Nor was it some sort of psychic skill that I tried to cultivate when I was doing the twelve-year-old apathetic thing, gleaning techniques from websites like LEVITATION MADE SIMPLE or books decrying LEARN TO LEVITATE IN ELEVEN EASY LESSONS.

Levitation happened after what Norah and I had called THE EVENT. Norah and I have also decided that THE EVENT should be in all capital letters. It is that big a deal. We don’t talk about it much, really. It’s all…

I had a dream about THE EVENT.

Or

THE EVENT sucked.

Or

Sometimes I think about THE EVENT all the time.

And so on.

Anyways, it took a while after THE EVENT for my mother to allow me to walk in town by myself without going into an overprotective frenzy. This is still true even in the daytime. She gives me pepper spray and a cell phone that has her number (#3) and the police departments’ numbers (local and county) on #1 and #2 speed dials. Norah doesn’t have a cell phone at all or I’d insist that she be #1.

Armed with pepper spray and a cell phone, what I usually do in the afternoons is walk to the bridge on the road to Acadia National Park. The bridge creates a narrow car path over a brook that babbles most of the year unless there’s been a huge storm and then that brook turns more into a river.

Once Mom started to homeschool me, I imagined that brook was like the one in the book, Bridge to Terabithia, which is a story of a boy, Jess, and a girl. The girl, Leslie, dies. That sucked. She drowned in the river. But the friendship part was cool.

They had a secret, magical world called Terabithia (thus the book’s name), which totally reminds me of the woods here. In the beginning of the book, Jess is cranky and depressed, but Lesley and her awesomeness helps him be happy and let all that negative crap go. I made Norah read the book too even though she completely prefers non-fiction narratives about Alexander the Great and his best friend Hephaistion. These guys were ancient Macedonians and conquered their known world. She likes doomed historical relationships. If you didn’t know, Alexander and Heppie were a thing. Anyways, like in the Terabithia book, my bridge is in woods. Pine needles cover the ground just beyond it. Ferns grow in groves, waving in the wind. The trees are tall and skinny and only branch at the top. So they are like super models—mostly leg and hair.

I wander around in here sometimes just imagining the way things could be. I’m wandering now when Norah finds me. She’s still got her bag from school, which is sort of a hipster Army-fatigue style, purposefully frayed.

“Hey,” she says.

“Hey.” I make my voice even deeper than it usually is and say like some house husband. “And how was your day, darling?”

“Well, dear,” Norah flips her hood back as she says this, “it was hellish. My AP Literature teacher— ”

“Mrs. Pearson,” I say like any good house husband. I rub my hand against the rough bark of a tree, feel it hum under my fingers.

“Yes, dear. Mrs. Pearson.” She gives an exasperated sigh. “We’re reading Faulkner, as you know, since you’re reading it too. Anyways, she insists that ‘monkey’ is not a racist term even when a privileged white male writer is using it to describe people of color and particularly African-Americans.”

I stagger backwards without even thinking about it, and I swear.

“Exactly.” She plops down on the ground and rests her back against a tree. “I wish I was homeschooled.”

“We could be homeschooled together.” This would be even better than me going to school actually because there would be zero competition for Norah’s attention.

“That. Would be. Amazing.” She leans her head back, lifting her chin up to the sky. The way the rays of light filter down through the tree leaves makes it seem like the Heavens are illuminating her. She has never ever looked more beautiful. “Cole? Earth to Cole?”

“Huh?”

“You’re zoned out.”

“Sorry.”

She pats the ground next to her for me to sit. “No big. What are you thinking about?”

About how beautiful you are. About how much I want you to always be safe. About how much I want you to be happy. About how much I want to kiss you and hug you and hold you and do people-in-love-things to you. About how I want to be the Jess to your Leslie, only without the death and adding in some sex.

“Nothing.” That is what I say as I sit down next to her. Pine needles jab at me through my jeans. “Nothing.”

Sometimes if you say a lie twice you come closer to believing it.

She immediately hops up again and I follow her. She touches tree trunks as she passes, flattening her hand against the bark.

“So, what are you going to do about Mrs. Pearson?” I ask as we meander through the woods.

She shrugs.

“Nothing?” I stop walking, shocked. Norah is a fighter. She never chooses nothing.

“I can’t educate all white people all the time, Cole.” She groans and rubs a hand across her eyes. “I told her in class. Everyone disagreed with me. What more can I do?”

“I think …” I stutter. “I think that this is a racist atmosphere you’re having to deal with. I don’t think you—you shouldn’t have to—Crap.”

She gives a weak smile and pets my shoulder. Her fingers are warm. I can feel the warmth of them even through the fabric of my shirt. “What more can I do? She’s already giving me a ninety in the class. I totally deserve a hundred.”

“Can I do something?”

“What?”

“Maybe go in there? Talk to her?”

“Like you’re my white knight or something? The white hero saving the day?”

Pain ripples through my head. Just outside the temple, but I try to push it away. “Is that sexist or racist?”

“Pretty much both.”

“But you’re my friend. How can I not—” The pain causes me to buckle a bit. Norah grabs me by the shoulder. I blurt before I can’t say anything at all, “How about I just kick her ass?”

“Cole?”

“I’m okay. Just a headache. Some knight.” I make my voice jocular and deep. “Sir Cole, who defeated dragons and evil wizards, was bested by his own head, downed by a headache of epic proportions.”

She smiles, shaking her own head. “You are silly and I worry about you.”

“Is that sexist?” I ask.

“Hardly. You’re the sex with the power, dork.” She grabs my head and starts slowly rubbing at my shoulders. “I think you’re tense. Tension causes headaches.”

I sigh. “I don’t want to be racist, Norah.”

“Everyone is. It’s just to different degrees and sometimes it’s because they’re ignorant and just don’t know they are being that way and sometimes it’s because they like to hate. People get addicted to hate.”

“But—”

“You wanting to help me is kind, Cole. It’s okay. I know it’s because I’m your friend, not because I am Black or a girl.”

“You sure?”

She laughs and it’s like magic. My head starts to feel better. Her hands stop kneading my shoulders and she grabs my hand and suddenly it’s like we’re a million things all at once—eight-year-olds again, an eighty-year-old couple, eighteen and in love.

“Let’s go deeper in the woods,” she says, standing straighter and looking into the distance, reminding me of the always brave Norah, adventure girl, from before THE EVENT. “Maybe there are unicorns there.”

“Or zombies?”

She shudders. “No zombies today. Mrs. Pearson is close enough. She looks so desiccated, you know? Like all the water has been sucked out of her. She’s like beef jerky.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“She’s disgusting.”

We walk through the trees, lightly breaking tiny twigs and underbrush, and once we’re completely on the trail, Norah almost starts to skip like she’s little again, but she catches herself and it becomes just a bounce. Turning, she smiles at me and it’s that kind of radiant smile you see on toothpaste commercials. It’s what my bonus dad Rick calls a ‘mega-watt’ smile.

She grabs my hand in hers and murmurs, “So cold.”

“Baby, you can warm me up.” I am only half kidding, but my voice is so amazingly skeezy that she can’t possibly take me seriously.

“Do you remember,” she asks without missing a beat, “when we were little and first started coming here and you made me read the Bridge to Terabithia book and then I made you read a book?”

“Yep. It was The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander.” It was a long, dry book—all about war.

“Yeah. That kind of sucked of me even though it is a glorious book that everyone in the world should read.” Norah reaches into her bag. “I got you something else.”

“Should I close my eyes?”

“No!” She grabs my shoulder with her free hand. “Stay here with me. Look.”

She passes me a small white book.

“The Chronicles of Narnia?” I whisper. “But that’s—”

“The book Leslie gives Jess in Terabithia. Yeah.” She nods at it and looks at me through her eyelashes. “When she told him if he read it—”

“He could learn how to be a king.” I pull the book to my chest. My skin prickles with the biggest happiness. It’s all I can do to keep my feet on the ground. My voice hitches and I force it deeper as I stumble-say, “Wow. Norah … I don’t know what to say.”

“Thank you!” She bops up on her toes and then back down again.

“Thank you!” I hug her into me, crushing the book in between us, but that’s okay because the book can take it. “You are the best gift giver ever.”

“Hardly,” she mutters into my jacket.

“Totally.”

She gave me the Alexander book right before THE EVENT. Our eight-year-old selves had walked down the Cromwell Harbor Road and then up to Kebo Street, past the golf course. Big maple trees made a curtain of leaves above the two-lane winding road. That’s where the man came. He wasn’t in a van. I always had imagined that bad guys drove old vans with no windows. I was wrong. This guy had a blue Toyota Prius, one of the first commercially-successful hybrid electric cars. He had stopped and asked if we were lost. He asked where our parents were. He said he had misplaced his puppy and asked if Norah could help him find it. He had a picture in his car. Norah is an animal lover. But he had no lost puppy.

It’s the oldest trick in the book.

We fell for it.

He lured her towards his car to look at a picture while he convinced me to wander over at the edge of the woods and yell for the puppy. I know this is groan worthy, but we were little. We were stupid. We didn’t realize that evil existed because all we had ever known was good. Evil rushed in though.

As twigs broke beneath my sneakers and I called out, “Puppy! Come here, puppy!”, Norah fought a demon. She managed to bite the hand clamped over her mouth and shrieked. Turning, I saw her legs kicking and flailing. Her shoes were untied. The laces flopped in the wind. It was like she was hovering there, fighting. Her sweatshirt flapped around like bird wings.

I was not usually a kid of action at that point in my life. Norah was. She was the tree climber and the one who dealt with bullies. She took care of things. She bounded and leapt through the woods as if she were a deer while I carefully picked where to put each of my feet. And that day? The day we met evil? That day, things changed. I screamed and ran towards them. I launched myself over the ditch into the car and slammed into the waist of evil, punching and flailing until he tossed me away. I hit my head on a stone, and when I did? That’s when the birds first came. Hundreds of them descended from the sky. Wings beat the air. Beaks tore at evil’s hair and clothes. Talons ripped into skin. They were small birds, but it didn’t matter. There’s a cliché that says there is strength in numbers and those birds had the numbers that evil didn’t that day.

The man let go of Norah to fend off the birds. None of them touched her as she sprinted to me, yanking at my arm, pulling me up so that we could tear away into the woods, cutting into a trail that led through trees, and eventually past backyards and a cemetery. A white dove led our way, flying right in front of us, leading us down the path. Behind us, the birds crowed and cawed and screamed, visible witnesses to the evil that was there, warning, warning it to leave us alone.

It wasn’t until we got to Norah’s house that the pain in my head became a pressure too big to fight any more and I collapsed by her swing set. The last thing I saw was the white bird, sitting on my chest, staring into my eyes.

“It will be okay,” I murmured to Norah.

She squinted in my face and her faraway voice started to yell for help.

But that was a long time ago and this is now and we’re still hugging and in a moment, she’s going to notice that I like her as more than a friend, so I gently disengage our bodies even though it is killing me to let her go. I know sometimes we have to let go to move on, right?

“Do you remember?” she says as if there is a possibility of forgetting.

“Yeah.” I don’t have to ask her what she’s referring to. It’s THE EVENT. It always is.

“Sometimes, I can’t get it out of my head.” She shudders. The trees above us have gotten so sad so quickly as she talks. They seem to wilt with each of her words, or maybe that’s just me wilting. “The way he touched me. The way you fought him.”

“You fought him too.”

“Neither of us was strong enough alone though.”

“It was the birds that saved you really.”

“Yeah. And you. You made the birds come.”

“We don’t know that.”

“I know that.”

The birds are here now. They alight on tree branches. They sing tiny snippets of song. They watch over us. Wings flutter. Talons hang onto wood, precarious perches.

“We are all precariously perched,” I say.

Norah jerks her head up to look at me. Her eyes are haunted. I know she’s remembering, but she doesn’t mention it again. Instead she asks, “What?”

“I was just mumbling to myself. You know, thinking aloud? I said we are all precariously perched like birds. A big gust of wind can knock us off our tree branch.”

“But we know how to fly,” Norah says, wrapping an arm around my waist.

“Yes. Yes we do.”

When I get home, Mom’s in the kitchen. She’s got a Pat’s Pizza box on the counter and the entire house smells like hot sauce and dough and pizza goodness.

“Pat’s?” I smack my butt down on a stool at the counter.

“No….” She snarks back and rolls her eyes. “China Joy. They disguise their General Tso’s chicken in pizza boxes to keep hungry passersby from mugging their take-out patrons.”

“So, we are still fighting,” I say this as a statement not a question.

She lifts her shoulders. They fall back down. She throws a piece of pizza onto my plate. “I just want to keep you safe. Why can’t you understand that?”

There’s a tapping on the kitchen window. The sounds come rhythmically and manage to be both light and insistent.

“Dear God …” she mumbles.

“Don’t look. The birds are just jealous because they have to eat seeds and worms and bugs.” I bite into the pizza. The warmth of it spreads throughout my mouth. It’s beyond good. “This is an explosion of awesome.”

She doesn’t answer, just keeps staring out the window. She stands up. One hand slams shut the pizza box. The other hand grabs my arm. “Honey, let’s go upstairs.”

“What?”

“Let’s go upstairs. We don’t need to eat down here. Let’s … Let’s …” She is obviously searching for words, her voice getting more and more frantic. “Let’s have a picnic! On the floor in the bedroom! That’ll be fun, won’t it?”

She doesn’t wait for my answer, just pulls me away from the counter. She snatches up the pizza box.

“Mom. It’s just birds. It’s okay.” I turn to tell the birds to stop.

She yanks even harder. “DO NOT LOOK!”

But I look.

No birds peck at the window. It’s something that is completely not birds.

“Mom?” I feel like I’m burnt, like I’m trying to get my brain to move through tall weeds and muck and I can’t quite get to a place where I can move forward to understanding.

“Come with me, Cole!” She pulls me again and I let her take me through the kitchen, up the stairs. She pulls our picnic quilt out of her bedroom closet, flutters it across the floor, takes the pizza carton off where she left it on the bed and then pulls down all the shades. It is like I’m five years old. But I’m not.

She plops next to me. We’ve left our drinks. We’ve left our plates. We have no napkins. She forces a huge smile and sighs out. “There, isn’t this fun? Just like when you were little.”

Her voice breaks on the last word.

“Mom …”

She bites into a slice of pizza.

“Mom …”

She chews. The house shakes in the wind. There must be a storm coming. She loves storms. She loves the way the world feels exciting. That’s what she always used to say. She doesn’t say it now though. She doesn’t say anything.

“Mom. I saw it.”

She meets my gaze with hers. “You saw nothing.”

“What was it?”

“Nothing.”

“Mom, I—”

Her voice rises about eighteen octaves. “There was nothing there, Cole. Do you hear me? Now drop it.”

I stand up and go to my room without a word. The pizza and my mother can hang out all by themselves. I slam my bedroom door behind me and flop onto my bed. I know what I saw tapping on the window: a skeleton with hollow eyes and an aching soul. It wanted in. It still does. The tapping? It keeps on throughout the night.